No, You Don’t Have Free Will, and This is Why

Slate recently featured an article written by Roy F. Baumeister, Do You Really Have Free Will? In it, he claims that human do indeed have free will, something that regular readers will know that I have emphatically argued against.

Baumeister doesn’t make any supernatural appeals in this article; he does not appeal to some sort of mystical “uncaused cause”. So how does he make the case? He does it by confusing “free will” with agency, that is, the ability to make decisions, especially those that involve human-level “self-control” and response to socially constructed rules:

Arguments about free will are mostly semantic arguments about definitions. Most experts who deny free will are arguing against peculiar, unscientific versions of the idea, such as that “free will” means that causality is not involved. As my longtime friend and colleague John Bargh put it once in a debate, “Free will means freedom from causation.” Other scientists who argue against free will say that it means that a soul or other supernatural entity causes behavior, and not surprisingly they consider such explanations unscientific.

These arguments leave untouched the meaning of free will that most people understand, which is consciously making choices about what to do in the absence of external coercion, and accepting responsibility for one’s actions. Hardly anyone denies that people engage in logical reasoning and self-control to make choices. There is a genuine psychological reality behind the idea of free will. The debate is merely about whether this reality deserves to be called free will. Setting aside the semantic debate, let’s try to understand what that underlying reality is.

There is no need to insist that free will is some kind of magical violation of causality. Free will is just another kind of cause. The causal process by which a person decides whether to marry is simply different from the processes that cause balls to roll downhill, ice to melt in the hot sun, a magnet to attract nails, or a stock price to rise and fall.

Baumeister does latch on to a meaning of free will that lay people who defend its existence often embrace. However, before I go into what’s wacky about this article (some of which should already be obvious), let me start with some of the things I like about it:

Living things everywhere face two problems: survival and reproduction. All species have to solve those basic problems or else go extinct. Humankind has an unusual strategy for solving them: culture. We communicate, develop complex social systems, engage in trade, accumulate knowledge collectively, create giant social institutions (governments, hospitals, universities, corporations). These help us survive and reproduce, increasingly in comfortable and safe ways. These large systems have worked very well for us, if you measure success in the biological terms of survival and reproduction.

If culture is so successful, why don’t other species use it? They can’t—because they lack the psychological innate capabilities it requires. Our ancestors evolved the ability to act in the ways necessary for culture to succeed. Free will likely will be found right there—it’s what enables humans to control their actions in precisely the ways required to build and operate complex social systems.

What psychological capabilities are needed to make cultural systems work? To be a member of a group with culture, people must be able to understand the culture’s rules for actions, including moral principles and formal laws. They need to be able to talk about their choices with others, participate in group decisions, and carry out their assigned role. Culture can bring immense benefits, from cooked rice to the iPhone, but it only works if people cooperate and obey the rules.

….

But very few psychological phenomena are absolute dichotomies. Instead, most psychological phenomena are on a continuum. Some acts are clearly freer than others. The freer actions would include conscious thought and deciding, self-control, logical reasoning, and the pursuit of enlightened self-interest

This is pretty accurate. Baumeister avoids “blank slatist” thought and recognizes that human abilities arise from the unique cognitive systems that humans possess. He makes it quite clear that these abilities don’t emerge from a vacuum but are the product of untold generations of evolution.

As well, as HBD Chick has noted, some actions and thoughts (or, more specifically some people) are more “free” than others – at least by this definition. Some people have greater ability to respond to externally imposed rules.

But, on that point, Baumeister doesn’t get into individual or group variation in these evolved processes that make decisions and regulate behavior (which vary greatly between individuals and groups). However, I will return to this point.

First I must address where Baumeister is clearly quite wrong. Particularly (and I suppose, unsurprisingly), like everyone who tries to defend free will in one fashion or another, Baumeister gets some facts about the world glaringly wrong (emphasis mine):

Different sciences discover different kinds of causes. Phillip Anderson, who won the Nobel Prize in physics, explained this beautifully several decades ago in a brief article titled “More is different.” Physics may be the most fundamental of the sciences, but as one moves up the ladder to chemistry, then biology, then physiology, then psychology, and on to economics and sociology—at each level, new kinds of causes enter the picture.

As Anderson explained, the things each science studies cannot be fully reduced to the lower levels, but they also cannot violate the lower levels. Our actions cannot break the laws of physics, but they can be influenced by things beyond gravity, friction, and electromagnetic charges. No number of facts about a carbon atom can explain life, let alone the meaning of your life.

These causes operate at different levels of organization. Even if you could write a history of the Civil War purely in terms of muscle movements or nerve cell firings, that (very long and dull) book would completely miss the point of the war. Free will cannot violate the laws of physics or even neuroscience, but it invokes causes that go beyond them.

Seriously? No, Dr. Baumeister (obviously not a physicist). Emergent properties – qualities that arise only in complex systems when many sub-units interact – are fully dependent on the properties of those sub-units. Life is completely explained by the “facts about carbon atoms”, “gravity and electromagnetic charges” (and the other fundamental forces). Let’s not forget, how these particles interact with each other are themselves facts about these particles. You’d just have a hard time describing and predicting the behavior of systems comprising these particles from their simple attributes as how they’re commonly thought of and taught.

Our description of events at higher levels of organization are merely shorthand for all the sub-forces that comprise them, such that if you wrote “a history of the Civil War purely in terms of muscle movements or nerve cell firings” it’d be a “very long and dull book”. It wouldn’t “completely miss the point of the war.” The point of the war would just be lost in the minutia.

Nothing in the universe “goes beyond” the laws of physics, and nothing about human brains or behavior “goes beyond” the “laws” of even neuroscience. It’s merely difficult to express descriptions of certain activities in terms of our commonly used wording of these basal laws.

You might argue that this is me being overly pedantic, but I think it’s important not to muddy the waters on these points.

Now what about Baumeister’s ideas about free will? I will show why even his new attempt to rescue free will by equivocation and redefinition still does not work.

The evolution of free will began when living things began to make choices. The difference between plants and animals illustrates an important early step. Plants don’t change their location and don’t need brains to help them decide where to go. Animals do. Free will is an advanced form of the simple process of controlling oneself, called agency.

In general, throughout this piece, Baumeister appears to be confusing “free will” with decision making, especially the sophisticated kind. Sure, scientists who criticize the concept of free will don’t deny that humans can make decisions. But here he makes a great effort to reinsert the “free” part in that process, a point made explicit here:

Does it deserve to be called free? I do think so. Philosophers debate whether people have free will as if the answer will be a simple yes or no. But very few psychological phenomena are absolute dichotomies. Instead, most psychological phenomena are on a continuum. Some acts are clearly freer than others. The freer actions would include conscious thought and deciding, self-control, logical reasoning, and the pursuit of enlightened self-interest.

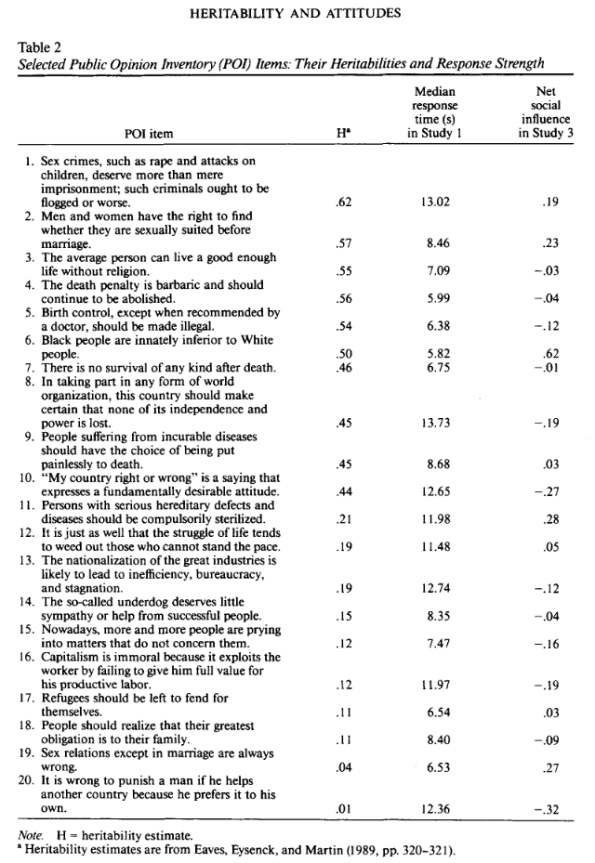

This is where he gets into trouble, and runs into conflict with thinkers like me on this topic. Even for the most sophisticated and profound choices, how “free” are they when the outcome of these choices can be predicted (at least statistically) by behavioral genetics?

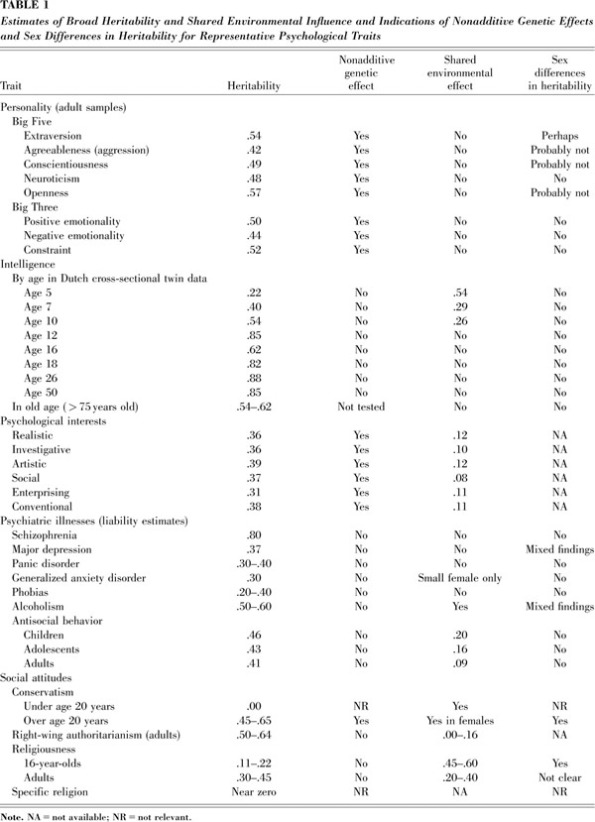

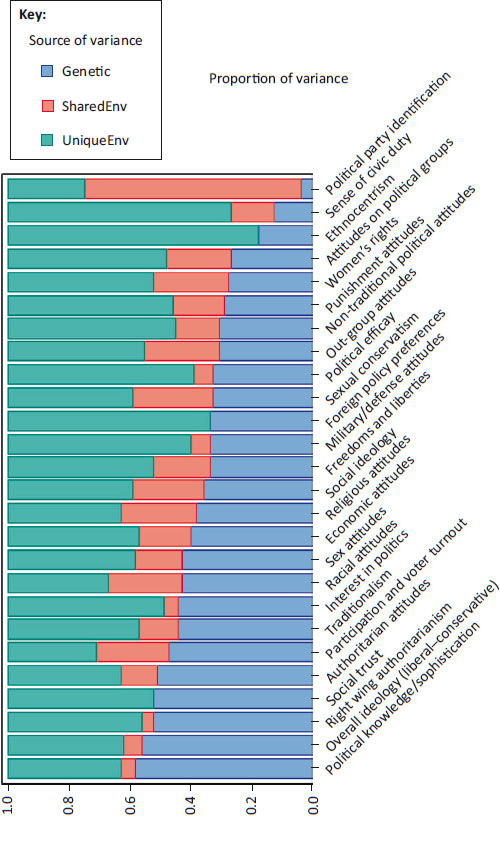

As we might recall, all human behavioral traits are heritable:

Human beliefs, attitudes, thoughts, decisions, and behaviors are all influenced by genes. Those things range from big things to small things – from trivial things to profound things. From the nebulous to the concrete, no matter what you think of, genes are in there somewhere. These include major life outcomes, as was seen in my previous posts on heredity and parenting. These outcomes that Baumeister would like to attribute to “conscious thought and deciding, self-control, logical reasoning, and the pursuit of enlightened self-interest” all turn out to be a smoke screen for path heavily set on its course by one’s DNA.

HBD Chick has said this perfectly:

from all the behavioral studies that are coming out of neurology these days, i just don’t see where humans are rational. that truly must be one of the greatest myths of our time. sure, some people are occasionally able to engage in some semblance of logic when they think about certain things, but the vast, vast, vast majority of humans are really running on autopilot — and even those of us who might just possibly have one or two neurons that can string together a logical thought — even most of us run on autopilot most of the time, too.

This process can even be demonstrated in real time as well. A clip from the ABC News program “Twintuition” featured behavioral geneticist Nancy Segal giving tests of shared thinking to twins:

The freaky concordance between identical twins in a variety of traits must give anyone pause before thinking their own actions are in any sense “free”. As Steven Pinker put it in The Blank Slate (emphasis added):

Identical twins think and feel in such similar ways that they sometimes suspect they are linked by telepathy. When separated at birth and reunited as adults they say they feel they have known each other all their lives. Testing confirms that identical twins, whether separated at birth or not, are eerily alike (though far from identical) in just about any trait one can measure. They are similar in verbal, mathematical, and general intelligence, in their degree of life satisfaction, and in personality traits such as introversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. They have similar attitudes toward controversial issues such as the death penalty, religion, and modern music. They resemble each other not just in paper-and-pencil tests but in consequential behavior such as gambling, divorcing, committing crimes, getting into accidents, and watching television. And they boast dozens of shared idiosyncrasies such as giggling incessantly, giving interminable answers to simple questions, dipping buttered toast in coffee, and — in the case of Abigail van Buren and Ann Landers — writing indistinguishable syndicated advice columns. The crags and valleys of their electroencephalograms (brainwaves) are as alike as those of a single person recorded on two occasions, and the wrinkles of their brains and distribution of gray matter across cortical areas are also similar. (p. 47)

…

the genes, even if they by no means seal our fate, don’t sit easily with the intuition that we are ghosts in machines either. Imagine that you are agonizing over a choice — which career to pursue, whether to get married, how to vote, what to wear that day. You have finally staggered to a decision when the phone rings. It is the identical twin you never knew you had. During the joyous conversation it comes out that she has just chosen a similar career, has decided to get married at around the same time, plans to cast her vote for the same presidential candidate, and is wearing a shirt of the same color — just as the behavioral geneticists who tracked you down would have bet. How much discretion did the “you” making the choices actually have if the outcome could have been predicted in advance, at least probabilistically, based on events that took place in your mother’s Fallopian tubes decades ago? (p. 51)

People do indeed take in information from their environment and the act of decision making is a very complex, intricate process that neuroscience has yet to unravel. Despite all this, this process occurs in predictable ways. This is because the space of possible outputs (i.e., decisions) is bound by the constitution of one’s brain, which itself is partially specified by one’s genes.

Hence, no matter, how you redefine it, calling this will “free” is simply unworkable.

OK, so how about the practical significance of this? Sure, we know that people aren’t completely “free” agents, but the thing most people care about when invoking “free will” is about responsibility. How “responsible” are people for their actions? Well, strictly speaking, people aren’t “responsible” for their actions at all. Even if the heritability of behavior was zero, since all actions have causes (such as, for example, the precise motion of the particle constituting one’s brain) which themselves at outside our ability to control, we can’t actually “control” what occurs.

But that’s from the perspective of contradicting the notion of the uncaused cause, which Baumeister agrees does not exist. What about on a more local level, with the idea that the concept of “responsibility” is meant to impinge on the decision making system of the brain and get it to modify its future behavior accordingly. As Baumeister describes:

Self-control counts as a kind of freedom because it begins with not acting on every impulse. The simple brain acts whenever something triggers a response: A hungry creature sees food and eats it. The most recently evolved parts of the human brain have an extensive mechanism for overriding those impulses, which enables us to reject food when we’re hungry, whether it’s because we’re dieting, vegetarian, keeping kosher, or mistrustful of the food. Self-control furnishes the possibility of acting from rational principles rather than acting on impulse.

Here is the crux of Baumeister’s whole argument. He is trying to weasel “free will” into being somehow synonymous with “complex” and “socially/morally considerate”. This is very much the idea most people have in mind when they invoke free will – that is, those who don’t invoke it for religious reasons. Unfortunately, as I’ve shown in this post, it doesn’t work that way.

As the previous data should make clear, “complex” doesn’t mean “mutable”. “Socially and morally considerate” doesn’t mean “not instantaneous”. Indeed, human decisions on even the most deep moral arguments can have a very “knee-jerk” quality to it, as the reaction times above make clear. To believe that “impulses” are somehow “unfree” but our more calculated, thoughtful decisions are somehow “more” free is to ignore the mountain of evidence we have the contrary. We are indeed running on “autopilot” most of the time, as HBD Chick would say.

But what about our ideas of “personality responsibility” and that oh so popular idea of “will power”? Well, the nonexistence of free will, even in this “Beaumeistian” sense, has significant implications there. We have rules and we have consequences for breaking those rules in our society because they do, impact the behavior of the people in our society (to varying extents)). Knowledge of the rules and more importantly, knowledge of the consequences for breaking those rules, enters into the decision making systems of the individuals in our society and gets the vast majority of them to follow the rules, most of the time. But we’d be fooling ourselves if we thought that we could simply “legislate” ourselves to any behavior we wanted. The existence of criminals demonstrates that individuals vary greatly their ability to respond to the incentives we have put in place to affect their behavior. Sure, we could get different results with different incentive, but the key point is that there are stiff limits to what we could accomplish with such.

The belief in the unlimited or at least much less limited plasticity of human behavior and decision making underlies many wrongheaded ideas in our society. Certainly ideas of diet fall under that category (for example, “fat shaming”). No matter how “free” you think people are, including yourself, you’re simply not. You’re a slave to your genes, your environment, and the circumstances you happen to be in.

(And I do mean environment. This post should not be taken to mean genes determine everything, which they clearly don’t. But as noted, you don’t need heredity per se to obviate the possibility of free will. If the “nuturists” were correct, and environment was the primary or sole determinant in behavior, your behavior would be largely “environmentally determined”; you’d be a slave to whatever circumstance in which you were reared. In short, you’re a slave to the wiring of your brain; how it got that way is secondary to this fact.)

Of course, while I say you can predict people’s behavior with behavioral genetics, you don’t really need science to see this in action. All you have to do is “know” people. All of us, when referring to someone we’re highly familiar with, has said that “I know [x person]” – meaning, we have a good idea how that individual will react – often in a detailed way – to a given circumstance. This, among many other things, should be a clue that free will, in any meaningful sense, simply doesn’t exist.

Previously:

What if it’s not their fault? The myth of free will.

97 Comments

Trackbacks

- The Constitution with Analysis and the Accessible Society | Handle's Haus

- Linkage | Uncouth Reflections

- linkfest – 09/29/13 | hbd* chick

- A Quick Note on Heritability and Changeability, Courteasy “misdreavus” | JayMan's Blog

- Free Will: Debate over Free Will is an End Time Deception | End Times Prophecy Report

- My Most Read Posts | JayMan's Blog

- Beware Armchair Psychoanalysis | JayMan's Blog

- The Derb on the JayMan | JayMan's Blog

- Red Pill Blues | Philosophies of a Disenchanted Scholar

- Human Biodiversity Weighs In On The Free Will vs. Determinism Debate | This Damned Life

- The Hubris of Scientific Determinism | Jim's Jumbler

- No free will, only biological determinism | Philosophies of a Disenchanted Scholar

- Free Will | The Z Blog

- A Failed Argument Against Free Will: Predicting Actions – William M. Briggs

Comments are closed.

This is uncharacteristically sloppy work by Baumeister.

The obvious analogy to human decision making is a computer running a program making calls to a sensor. All the Sci-Fi talk about AI and the singularity should make this analogy more obvious in common parlance, let alone philosophical investigation. Even a lego-mindstorms device can do squirrel-like things and receive data about it’s surroundings, interpret and process it, and make complicated decisions on that basis about what actions to take next. But we live in the age of Siri, self-driving cars, ultra-smart / ultra-complex search engines, big-data handlers, and ultra-sophisticated Bayesian prior-updaters that learn about the world in a progressive manner, adjusting and refining their models and notions of causality as time goes by and more evidence is received.

Is google’s server farm and like applications complex enough to rise to ‘free will’? Why not? They handle tasks in microseconds that no human could possibly accomplish. Describing the civil war in terms of carbon atoms is no different than describing interstate traffic consisting solely of automatically-driving cars in terms of silicon atoms. What distinguishes a program from genetic predispositions and neurological biochemical processes?

My intuition is that ‘most people’s opinion’ (a horrible authority, but the one to which Baumeister himself makes appeal) would reject any of these complex decision-making computers as having ‘free will’ – so most of what Baumeister wrote seems utterly besides the point.

Sentience, Consciousness, and Self-Awareness, seem more along the lines of what most people would need to be willing to adjudge a computation system as having ‘free-will like’ properties. Self-re-programming, or at least Bayesian updating, is also a must.

But, what I really think ordinary people are getting at when they talk about free will is the feeling of grappling with a hard decision, especially trying to summon the discipline and willpower to deny indulging in a detrimental temptation. We have this grappling experience with results that do not seem to be deterministic and, again, to an ordinary person, if that experience is not part of a process where we are exercising ‘free will’, then what is it? Or, how would you explain it to them. Does it have a good evo-psych story?

@Handle:

Very well said!

“I can resist anything except temptation.” Oscar Wilde

I would explain it to “them” (the Ordinary) thusly: maybe we have a built-in mechanism that causes us as human beings to believe our actions are “free” – or as you’ve stated that “grappling with a decision” is evidence of free-will, or for that matter invoking willpower is an example of free will. The more interesting question is, why do we have such a mechanism? Why must we believe that our choices are, in fact, choices? Dogs and cats and other perfectly good mammals don’t have such a mechanism . . . or (yikes!) do they??!? Someone below speculated it had to do with procreation . . . perhaps we’d lose motivation to procreate if we didn’t think we had a lot of choice about it. Which is funny, since when it comes to rational choice, procreation is one of those things we often have the least rational control over.

The fact that we even have a word called discipline, begs the fact that we live in a Deterministic universe. That word would not exist. Many phrase, ideas, and institutions give our determinism away; like the phrase “I just couldn’t help myself.” Why did you think you ever could?

To someone still believing they have freewill I’d say consider two things; (both I’ve borrowed from Sam Harris) You have about as much control over the next thing you think as the next thing I write. Where does freedom fit into that? Also, are you free to do things that don’t occur to you to do? And if you “decide” upon two alternatives, to look back and say that you could have chosen differently is to simply state that “I would have “chosen” differently IF I had chosen differently.” Really, you had no choice at all. Only what can happen, will happen. I strongly believe that we’re ENTIRELY automated. Not only does our heredity and environment dictate us but the above lessons in consciousness that I mentioned seal our automation totally. Thoughts arise unannounced, uninvited and force us to do things before we even consider doing them. People who argue for Free will either can’t reliably understand the human condition or have some axe to grind that would dull if people knew they were automated.

My acceptance of my own automation has been exceedingly helpful in becoming sober after years of alcoholism. I have a peace of mind and an understanding of my brain that no religious zealot can enjoy free of delusion.

The funny part is that you can use determinism as a way around step 3 in recovery models. As an atheist and Sam Harris fanatic, this was important to me. I don’t have to foolishly try “giving my will and life over to the care of god” when I see I have no will anyway!

@Neptunutation:

Beautifully put!

I think your thinking on this subject is a cross-purposes with mine (rather than actually contradicting it), and I find this kind of lack of meeting of minds is typical of the free-will debate. To me, ideas of uncoerced decisionmaking and unimpeded will form a perfectly adequate concept of free will that has nothing to do with uncaused causes or subatomic-particle-level determinism.

From my point of view, the fact that twins may make identical choices has no bearing on issue: the question is, were their decisions freely made, or coerced? (obviously, there’s a continuum.) That is, after all, what people mean when they ask whether someone did something of their own free will.

@Jayman

1) You would have to define your criteria for ‘free will’, using some scale such as completely unfettered at one end and entirely deterministic at the other.

2) Certainly, our PREFERENCES and ABILITIES are bounded genetically both as an individual and as a species.

3) Equally certainly, it’s not PHYSICALLY POSSIBLE for our thoughts to be thoroughly deterministic for reasons I’ve argued elsewhere but will repeat here if necessary.

4) That we are bounded does not mean that within those bounds of our senses, perceptions, apprehensions, and rational abilities, we cannot make decisions by our own will. It does mean that we will produce categorically similar decisions. But categorizing those decisions as similar is an artifact of the same processes, and therefore appears more deterministic for the same reason.

The reason our decisions are categorically similar is that most decisions are unclear and require guessing and guessing is heavily weighted by intuition, and intuition is very heavily genetically biased – which the twin studies illustrate.

That we produce similar decisions because of biological factors is different from saying that we cannot choose differently if we are aware that the choice is in itself a test of free will. And most studies prove this, and the problem of measurement in the social sciences is largely driven by the need to eliminate this awareness so that the results are unbiased by the question.

5) I have spent quite a bit of time on this problem and while I think in the large I agree with your sentiment that our gene expressions, pedagogical experiences, normative biases, and general knowledge tend to produce categorically predictable results, that is very different from saying that we cannot choose to make alternate choices that produce DIFFERENT results. We demonstrably can. As such, the question is better stated as an information problem. People are open to persuasion given sufficient knowledge and incentive. But ignorance simply encourages that we rely on intuition out of calculative efficiency. Where I use “calculative” in the broadest sense: as choosing between sets of “anticipations”.

Most of the time, humans choose that which has the greatest benefit in the shortest time with the least effort, with the greatest chance of success at the lowest risk. Any organism must do that. But if we change the ‘greatest benefit’ to something trivial, like, a test of free will, we can demonstrate free will.

Cheers

Curt

@curtd59:

No. Free will ≠ lack of determinism. Even in a “random” world, free will would not exist.

In any case, this makes little sense, because the world isn’t deterministic, ala quantum mechanics. The world is “probabilistically deterministic”; the exact course of events we perceive is random, but that occurs within a probability function that evolves deterministic way.

But why do you make the decisions you do? That’s the key thing and the reason there can be no free will.

We can? There is no way within our technological capability to demonstrate this.

Well, if the grotesquely obese cannot help being so, then I suppose I cannot help but deride them.

“Fat-shaming on autopilot.”

Sounds like my epitaph.

I’ve always thought that if I were a judge, and a defendant tried to convince me that because he didn’t have free will, he shouldn’t be held responsible for his crimes, that I’d reply “Since I, too, lack free will, I have no choice but to find you guilty and sentence you to …”

@Anthony:

In most contexts you’d be justified in doing so.

I’d like to see some twin studies with one twin raised by Jesuits, the other by crack dealers.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarnoff_A._Mednick#Criminal_behavior

I think the basic problem here is a that people think that if they don’t have ‘free will’ then they are slaves. They feel free, they want to be free and therefore they must be free. They then set about coming up with whatever mental acrobatics are necessary to explain why they are in fact free. It is of course absurd but it flows naturally from the reality that we are hard wired to think in certain ways, that we have neural heuristics aplenty working furiously to make sense of input, casting it all in the best possible light for our own survival. My guess is that the reason people widely believe in free will is because this particular delusion makes them feel good about themselves, possibly aiding procreation in some way. Would you wants to make more little Billy’s and Suzie’s if they’re just mechanistic robots? (Maybe this isn’t the right place to ask this question but you get my point.)

I have a guilty pleasure where I see how long it takes in conversation before I can start predicting a person’s innermost feelings about things which I will then occasionally blurt out to see what they’ll do. Generally it’s not very long. Most people are so mundane, so simplistic in their thinking that with a combination of their emotional demeanor and how they approach conversation with another person, I can get the gist of who they are in moments. The fact that anyone can learn cold reading (though not everyone can become great at it) should point people to the fact that the human herd is as a rule, not terribly interesting, but alas most refuse to believe that cold reading even works. I have a ton of friends who think I’m secretly a psychic, it’s sad really.

~S

@Sisyphean:

Great points.

“and even those of us who might just possibly have one or two neurons that can string together a logical thought — even most of us run on autopilot most of the time, too.”

Oh and as an aside, I’d be careful with thinking that being smarter and more logical makes a person less predicable, more free. I’ve noticed this belief to be quite common amongst intelligent folk… You might even say it’s predictable. Yes, I have a terrible habit of burning nearly every bridge I come to.

~S

@Sisyphean:

No, my man, you’re quite right. Smarter people are more sophisticated and more nuanced. But they’re NOT any more “free”.

Haven’t read the article yet but would like to give you my considered view as a 72 year old man: I think we (most of us) have free will going forward but looking back over my life I get the feeling that all the big decisions in my life, the ones I really struggled with, were in fact preordained given my personality and experience and the opportunities before me, at least as I perceived them.

OTH, you could argue that people with extremely short-term time horizons don’t really have free will. If you can’t respond to incentives or the likely consequences of your action, especially where criminality is concerned, in what sense are you free? You still should be locked up though. In fact that might be precisely why you should be locked up.

Now I’ll read your post!

Nothing in the universe “goes beyond” the laws of physics, and nothing about human brains or behavior “goes beyond” the “laws” of even neuroscience. It’s merely difficult to express descriptions of certain activities in terms of our commonly used wording of these basal laws.

Well, now, you are making me change my mind. The laws of physics are laws of probability. Thus chance plays a very large role, even in human decisions. Maybe if we were placed in the same situation twice — I’m talking about those really big decisions, like what am I going to do with the rest of my life — we would decide differently. As long as it felt like a decision you could say it was free. In physical systems we talk about “degrees of freedom.” Maybe something similar applies to human behavior.

@Luke Lea:

Luke, you’re falling victim to the idea that free will exists in some sort of mutually exclusive dichotomy with determinism, such that if events in the universe could be shown to be not perfectly deterministic (which they aren’t), then free will must exist.

However, it doesn’t work that way. I’ll quote Steven Pinker to give you an idea:

(pp. 177-178)

Quantum randomness doesn’t mean that the uncertainty inherent to the physical world is the freedom that living beings have to decide; you decisions still come down to the luck of the subatomic draw.

Not in any meaningful sense. You should research split-brain patients. That you think you are making a free decision, with all the thought that goes into it, is all part of the process – a process which is largely invisible to you.

Well, I don’t think anything is “beyond” science. It’s all merely a matter if we can answer the question with the tools we have available.

Give it time.

I recently had this discussion over at one of my other posts. Yes, induction, and hence all science, is based on an article of faith. It is however a faithful belief that has proved to be incredibly useful. Since no one has cooked up a better system, I’ll stick with that. 🙂

In this case, as long as you’re going on that article of faith, free will simply does not and cannot exist. 😉

Even for the most sophisticated and profound choices, how “free” are they when the outcome of these choices can be predicted (at least statistically) by behavioral genetics?

Precisely. And I think you may be digging your own grave here. The degree of uncertainty is the degree of freedom. Which is why the conundrum of free will will never go away. You are liable to change your mind about it several times over the course of your life. Which one of your opinions can you say will be true? Only the current one, for now.

Final remark: this is not a scientific issue. It is beyond science. Or, if you prefer, undecidable. There are plenty of things beyond science. The phenomenon of consciousness itself for example. Or if that is too abstract, take physical pain, which is about as concrete as you can get in the world of subjective experience. We can never prove that other people’s pain is real. Science deals with the objective world, which is the world about which two or more subjective minds can agree. We can never prove that the other mind is conscious like our own. This is straight out of Popper. And then of course there is Hume’s paradox over the principle of induction, upon which all science rests. You cannot establish the principle of induction without appealing to it in the first place. It is a matter of faith.

Edit for clarity: “Science deals with the objective world, which is the world about which two or more subjective minds have simultaneous access.”

The problem is that the human brain is built to think in terms of agency and free will. We think, “now I will go out in the shed and fix my bicycle” rather than “all the causative circumstances in my current situation will have the consequence of me fixing my bicycle.” Our wiring and our general situation forces us to think as if we had free will. We always make decisions under the assumption that we get to make them, rather than that there is one inevitable outcome.

I suppose I’ve worn out my welcome (sorry, Jayman, couldn’t help it) so here is Samuel Johnson on the subject:

http://www.samueljohnson.com/freewill.html

From the standpoint of Quantum physics, the Universe is actually not deterministic.

@Dan:

Indeed. That has nothing to do with the existence of free will, however.

Jayman, I don’t think determinism means what you think it means.

I counted 16 instances in your post of the word ’cause’ in one form or another, not including ‘because’. You agreed that the universe is not deterministic. That is just another way of saying that the Universe is not strictly causative. And yet strict causation is the axiom upon which the above argument is built.

If the axiom isn’t true, there is a slight problem with the proof.

@Dan:

No, all actions have causes. It’s just that the “effects” of those causes are inherently probabilistic. That is, for a given event, there is a range of possible outcomes. Because of the interdependency of the “outcomes” of these events that occurs in large systems, we witness only one of those outcomes for a given event. (This is essentially a statistical consequence

; because the random events that occur at quantum scales have consequences for larger collections of particles upstream, such large systems must “agree” on an outcome. Hence, what we observe.)

“all actions have causes”

We can’t strictly say that. The ‘proof’ that we don’t have free will is premised on the precondition that given all of our present state, a specific outcome is predetermined. But that is just not so. The initial state for us emphatically does not dictate a particular outcome.

If a particular outcome occurred or a particular decision was made by a person, we cannot say that is because of our initial state, that outcome had to occur. In fact you could start with exactly the same initial state all the way down to the subatomic scale and get a completely different outcome. How can you say the initial conditions ’caused’ A to occur when the same initial conditions could have ’caused’ B to occur?

“It’s just that the “effects” of those causes are inherently probabilistic.”

Probabilistic ‘effects’ are not effects in the real world until, as you say, an outcome is agreed upon. But then the final answer is either one or the other. The probability is not the answer. It is just a middle part of the calculation, like the square root of negative one. Imaginary numbers are useful in the mathematical realm but the imaginary part must drop out to get an answer we can work with.

Similarly, it is not correct to say the outcome is a probability.

@Dan:

You’re going to argue with quantum mechanics? Good luck. 😉

No. As I explained, the non-existence of free will is indeed predicated that all actions have causes, but it has nothing to do with there being one “pre-determined” outcome. In fact, as per quantum mechanics, there are many possible (infinitely many, in fact) outcomes for any given event, each of which having some probability of happening (some more than others).

The is the meat and guts of the quantum implications here, yes.

Umm, double slit experiment?

(For the record, not a very good example. Imaginary numbers (which are poorly named) are just as “real” as real numbers. It’s just that they weren’t considered in our number system until a use for them (solving quadratic equations) was discovered. See here.)

It is correct for the reasons explained above. I’m not talking about measurement imprecision driven probability (which would be borne out of our ignorance of the initial conditions), I’m talking about true probability, the kind that would emerge even if we had perfect knowledge of the initial conditions of a system.

As I explained above, even with quantum randomness, free will still does not exist, because a somewhat random universe merely shift the cause of decisions from being the result of strictly set initial conditions to being the result of random events – both of which are equally beyond our “control”.

@Jayman — I did study Quantum at Cornell, while studying Applied and Engineering Physics, so I’m not entirely out of my depth. Pray tell, what is your educational background re physics?

In any case, a background in physics should not be necessary for our discussion.

Thank you for bringing up the double slit experiment because that is perfect for our discussion. Or the single slit for that matter. There is a probabilistic function for a photons that go through the slit which leads to the funny illumination pattern on the screen that we all recognize.

However, a single photon does not exhibit a probability in the end. The single photon winds up at a single point. The probability is merely predictive. Probabilities are not real. The result is real and it is singular, with a final probability of 1 at one point at zeros everywhere else.

Similarly suppose I have a decision to make, either ‘A’ or ‘not A’. Even if my initial state is known down to the subatom particle level, sometimes my decision will be ‘A’ and sometimes it will be ‘not A’ for quantum reasons.

One cannot say that my decision was caused entirely by my initial condition, because it was able to go either way. There was another factor, a Quantum unknown (or unknows). The proof is not possible without a closed system.

You may try if you like to claim what you want to about the quantum impact, but all that an honest physicist can honestly say about it is that it is unknown. A good scientist is willing to acknowledge the boundaries of what he knows.

@Dan:

No disrespect, but most people who learn about quantum mechanics don’t learn about its implications. 🙂

You’re stuck thinking like a classicist here; that the every event must have one fixed and guaranteed outcome. It doesn’t work that way, and there’s no reason a priori to assume that it need work that way. The reality of the world shows that events inherently have a range of possible outcomes, that’s to the inherently probabilistic nature of the particles which comprise the universe.

Hence, yes, your decision was indeed caused by your initial conditions, within the range of possibilities as bounded by those initial conditions. You decision was also caused by the state the particles so happen to take. The inherent roll of the subatomic dice.

Indeed.

And it will be both A and “not A” until the outcomes of larger systems force a “determination.” Schrodinger’s Cat?

No. The interference pattern will still appear even when single particles are shot, one at a time. Sure, the photon/electron does appear at a final point, but each particle appears to travel through both slits simultaneously. What’s the probability then?

You’re actually playing this game yourself here. First of all, where did these “quantum unknowns” come from? You seem to be invoking Einstein’s “hidden variables” theory, which has never been verified. Again, there is no reason to believe a priori that the universe requires some form of determinism.

Look, the whole reason we see something being “A” vs “not A” is because our world is the one where “A” or “not A” occurred. This is the “Many Worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics. Some thinkers on the matter will try as they might to deny this, but this is the only possible solution to the observed quantum phenomena. It’s not really hard to see why, so long as you let go of necessary classical determinism before hand.

The reason for existence of the many worlds is that each represents the configuration of matter with particular quantum outcomes. What we perceive as the passage of time is the “flow” from one quantum state to the next. All the quantum states “exist” simultaneously. We appear to experience “one” discrete history because history, as we know it, follows the path of the “agreed upon” states the particles that comprise our moment of reference have taken.

However, coming back from the nature of quantum mechanics, this discussion is besides the point. There is still no free will even in a random universe, because then the decision you make are the result of the “paths” the particles which comprise you so happen to take. In short, random events “decide” your actions, not “you”.

Jayman,

I find it very difficult to debate with you because when you become vested in an argument, you tend to weaken your scientific mindset. By scientific mindset, I mean being able to keep the distinction clear between what you have proved to be true and what you theorize but have not reached yet by definitive proof. Those who have plowed through lots of difficult physics and math problem sets have a better ability to keep this distinction clear.

(I discovered this when debating with your germ theory of gayness. It is an intriguing idea but the boundary between what is thus far shown and what we don’t yet know based on positive evidence was not kept clear.)

With respect to ‘quantum unknowns’ I am merely saying that we don’t know where quantum variability comes from. It is an unknown. Nobody has ever been able to explain it. If you can, a Nobel will surely be yours.

It seems like the statement you are totally unwilling to make is ‘I don’t know.’ I have no problem admitting that.

I am not insisting on free will and don’t claim to prove it. I merely note that there is this unknown source of variability. If quantum variability is not unknown to you shouldn’t be here arguing on a blog. Publish and get your Nobel like a champ!

The Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI) is a mere theory which was created precisely because it restores determinism (and your relying on it is therefore begging the question), but it has not an iota of positive evidence for it. From the perspective of simplicity (i.e. a ‘beautiful theory’) it is a mess (MWI is far as you can get from Occams Razor) and the main reason people like it is because it restores determinism.

You say about MWI, “Some thinkers on the matter will try as they might to deny this, but this is the only possible solution to the observed quantum phenomena.” Not true at all. MWI is not the leading theory, not even close and it is not even in second place. The Copenhagen Interpretation is the leading theory (although there is nothing close to agreement here) and it is open to nondeterminism.

http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2013/01/17/the-most-embarrassing-graph-in-modern-physics/

As a scientist, I prefer the Copenhagen Interpretation because it just accepts what the data says and then stops. It is the most honest theory to me because it merely goes as far as we have observed and avoids speculation.

Quantum variability is a big problem if you want to foreclose on free will. One could easily argue that quantum variations are intrusions into our realm from a so-called spirit world, or you could say that quantum effects are themselves are a manifestation of our choices.

I am not making this argument. I am just saying that I see no way to prove these things false. There are these quantum variables everywhere and nobody I know of can say what they are or can explain them beyond probabilities. If you can, get thee off this blog and claim thy prize money!

@Dan:

I wouldn’t assert a position, especially in the strong form, if I didn’t believe I had a good reason to do so. As always, that reason would be the evidence.

So it seems that you, broadly, agree with my post, largely for the reasons I state. What we are discussing here then goes beyond the scope of this post. Which is fine. And on that.

The Copenhagen explanation is complete rubbish. The problem is that is an attempt to reconcile quantum phenomena with our naive belief about how the universe should work. Needless to say, trying to assert that the Copenhagen interpretation is true merely because it’s the most popular with physicists is an appeal to authority.

Actually, the reverse is true. The Copenhagen view asserts all sorts of of its own extraneous propositions, such as wave function collapse, physical laws being inconsistent on different scales, and a central ontological role of conscious observers, all of which are unverified and contradict what we understand about physics.

At the same time, Many Worlds merely asserts that we take what we see at face value; it perfectly explains what we see, and doesn’t lead to insert a bunch if fudge factors to explain the results.

What is simpler, the Copenhagen with its many new entities we need to accept or Many Worlds with no such propositions at all? The extra universes naturally follow from what we see, so it’s hardly an unnecessary multiplication of entities. In any case, see this excellent description of the situation:

Q: Which is a better approach to quantum mechanics: Copenhagen or Many Worlds? | Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist

Your view on accepting what the data says and leaving it there apparently greatly differs from mine. 🙂

Also, check out Max Tegmark’s work on the matter.

We could say this, but there is no evidence for such. That’s Matrix territory at that point, and hence of little utility here.

The status on the existence free will is clear. The problem lies not with what we know, but what people are willing to accept. The latter isn’t really my concern when assessing the truth.

But in fact I could adhere the the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI) and still see how free will could occur. What if we live in a ‘choose your own adventure’ system where each person’s choices are reflected as quantum variables that send him or her into the universe of his or her choosing?

I’m not insisting on this but I can’t prove it false either. I don’t think it is true, but I haven’t got the tools to answer definitively one way or the other. If you can answer questions like this, you must graduate from this blog and seek your glory!

@Dan.

But Many Worlds is still incompatible with free will, because it’s not “you” deciding, just each iteration taking its path. 🙂

People keep saying quantum physics proves against determinism. THIS IS UNTRUE! Just because WE can’t predict where an electron will be doesn’t mean it’s impossible. In fact, seeing as everything else is predictable, it would be crazy to say that its all chaos on a small level. It isn’t, people are just vain and dramatic. We’re not yet technologically advanced enough and have only just barely stumbled upon quantum physics studies. Under unobtainable observation methods, we could watch and predict how everything happens in quantum physics. People just like dramatic words like “Chaos” “random” “unpredictable” because it all caters to mysticism and the stubborn place people love to be in which is “the unknowable.” These people are no different than religious people who dont want to know. Thats the difference between enjoying ignorance the way that scientists do (seeking to know more) and the way that mystics do (denying that anymore can be known) (they dont want to know and would rather say its unknowable—-bullshit!)

Columbus thought he was in India for at least a month or two! We study quantum physics for 50 years and everyone is suddenly an expert? LOL Everything has cause and effect. People fall for the same delusional tricks and petty psuedo scientific journalism every time!

@Neptunutation:

No it really and truly is impossible, as per the physics. It’s not a matter of technological limitation, this is a real physical limit.

Indeed. But one of those causes is inherent randomness.

With respect to your blog and you. I hardly think you can definitive about that. Scientists routinely adjust theories and especially in a brand new field (quantum physics) where speculation fills every corner, finding out tomorrow that electrons do have a predictable course would make perfect since everything else in universe also has a predictable course.

In this case, yes you’re right, currently our scientists say that an ‘inherent randomness’ lays upon physics BUT, like I said before. The fat lady hasn’t sang by a long shot. The definition of random is meaningless like the word miracle. And also to my first point, there are way to many variables present to say that is random when we cant find a pattern. That’s bullshit bro. First of all, we still don’t know why gravity works or how to exploit electromagnetic force to the fullest. Forget about the strong and weak force. There are way to many uncertainties and unsolved for affecting agents to say that reality is at its core random. That literally sounds exactly like mystics saying bullshit like they can fly or have spoken with the creator of the universe. It is dramatic and immature conclusion that doesn’t make sense intuitively or rationally.

I think you and would agree on much and Im glad you read Sam Harris. It seems like we both agree that freewill is bullshit. I just happen to know that Im entirely automated in every way and so is the universe (whether I can prove it or not)

To say that its all truly random is like saying that the speed of light is 186,000 mps everywhere in our universe except for in Andromeda where it goes twice as fast. Either youre a determinist in every respect for the whole enchilada or you can start rethinking your freewill convictions. If what youre saying is true 200 years from now, then Id renounce any argument the no freewill exists. You cant have it both ways.

Its pretty ignorant to believe in randomness. Its simply impossible Jay. Have a good day.

@Neptunutation:

Your own personal incredulity is fine and good. You’re free to choose not to believe. But, to be frank, you don’t know what you’re talking about. Please don’t bring up this particular matter here again, thanks.

How can you be a Harris fan, argue for Determinism and that free will is illusory but then turn around and say that random things make up the physical world?

I’m not the one who doesn’t know what he is talking about. You are the one who shouldn’t comment here because your view is hypocritical and contradictory.

Either everything is determined and automated or it is not. There is no middle ground. If our smallest parts aren’t determined then how can we be?

I’ll comment where ever I want too so shove it.

@Neptunutation:

Maybe somewhere else, not here. Moderation (not banned only because I’m feeling generous).

This is the question not actually about free will, but about the existence of the conscience. If my acts and thoughts are effects of the brain wiring, then how can I claim that I exist, and by that I do not mean my physical existence: the feeling of heat in my hands hitting the keys on my laptop, pain in my back, weight of my glasses on my nose — I mean the psychological processes I experience and I observe, the very act of “experiencing” and “observing”.

@szopeno:

Well, what does it mean to “experience” or “observe”? What do it mean to have sensation? These are actions registering in your brain that set off a cascade of activity that produces “you”. I invoke Steven Pinker a lot, and his book The Blank Slate, but it really is good reading to understand the concept. Particularly, there’s a section where he talks about the modular mind, especially studies of people with “split brains”, that really shines a light on the matter.

The conscious does exist but the “self” “me” “I” does not. This is what Sam Harris’ new book is about. Picture the conscious as a cylindrical mirror. Its always rolling and reflecting our emotions, thoughts and motives but those are just reflections on the mirror rolling in and leaving just as fast. they are illusory. They are NOT the mirror. The mirror is just the mirror when it’s not reflecting self, emotions, thoughts etc… This is what true meditation is, practicing “not reflecting” all that crap but to actually pay attention “free from thought” to conscious.

I hope this helps. I agree that this is all really about consciousness. Our lack of Free Will is just the most obvious observation in trying to meditate. I think its important and requires no idiotic presumptions about the universe being created or us having souls. We just need to practice paying attention to our conscious rather than being in religion. I’m atheist.

@Jayman, you should read “Defense of Socrates”. You have just invoked the exact answer which was ridiculed by Socrates. The explanation does not really capture “experiencing” feeling “I” have. The explanation that the experience changes my brain structures does not really explains what an experience is for me.

BTW, what is your definition of “free will”? Because it seems absurd if that definition would not suit to what common people think, when they say they have “free will”.

Mr Jayman, have you read “Identically Different: Why You Can Change Your Genes”? Tim Spector – using fascinating case studies of identical twins – draws gems from his exhaustive research project that has spanned twenty years to show how even real-life ‘clones’ with the same upbringing turn out in reality to be very different.

Based on cutting-edge discoveries that are pushing the frontiers of our knowledge of genetics, he shows us that – contrary to recent scientific teaching – nothing is completely hard-wired or pre-ordained. Conceptually, he argues, we are not just skin and bones controlled by our genes but minds and bodies made of plastic. This plastic is dynamic – slowly changing shape and evolving, driven by many processes we still cannot comprehend. Many of the subtle differences between us appear now to be due to chance or fate, but as science rapidly evolves and explains current mysteries we will be able to become more active participants in this human moulding process. Then we can really begin to understand why we are who we are and what makes each of us so unique and quintessentially human.

@Mac:

No, but I’ve read Judith Harris’s No Two Alike which is about the same topic and approaches the matter with extensive evidence and offers a hypothesis that may explain the results.

That’s mostly a bunch of squishy nonsense. Yes, there are indeed brain functions that are “hard-wired”. But that genes and environment interact in complicated ways to produce the final product is clear.

Perhaps. Much of the differences between identical twins – perhaps the vast majority – stems from developmental noise. In other words, chance, in fact.

Indeed, in time. Thanks for the book suggestion! 🙂

Jayman: Nothing in the universe “goes beyond” the laws of physics,

If physics means “that-which-constitutes-and-governs-the-universe” and universe means “all-that-is”, that seems tautological and something anyone could say, including a theist. If it’s not tautological, how can you be certain it’s right, i.e. that there isn’t something outside the universe (in the currently accepted sense) that influences it? I wonder, though, in what sense mathematics goes beyond, or logically precedes, the laws of physics. As far as humans are concerned: being aware of pi or sqrt(2) or the infinitude of the primes isn’t something that, in any direct sense, comes thru the senses or thru matter. Even if Tegmark is right and all mathematical objects physically exist somewhere in some sense (I don’t agree), that isn’t how human beings are aware of them. Our brains work because of the laws of physics, but they grant us something beyond matter that isn’t obviously derivable from physics-as-phenomenon. In fact, physics-as-subject is beyond physics-as-phenomenon.

and nothing about human brains or behavior “goes beyond” the “laws” of even neuroscience.

Yes, but there is something very mundane but very mysterious in, or of, the brain: consciousness and its role in cognition and behaviour. Is it causal or simply epiphenomenal, for example? Scientifically speaking, consciousness doesn’t seem necessary and doesn’t seem possible to explain. It may never be possible to explain scientifically or to confirm objectively, rather than from the inside. If it’s a product of (a particular sub-set of possible) material brain-states, why don’t the brain-states suffice on their own? Do they suffice on their own in some people or could they suffice, if modelled electronically or mechanically? And if consciousness is simply epiphenomenal, is being conscious of being conscious etc an illusion? It doesn’t seem to be, but how is a brain-state aware of itself or aware of its own (non-material) product? N.B. I am a strict materialist and don’t believe in the supernatural.

@Magistra Mundi:

That would then make the problem one of semantics, yes? Specifically, what do we mean by “universe” and something that is “outside” of it?

Well, look at it like this:

Brains do? What evidence is there of that?

Since we have it, and since evolution apparently went to a lot of trouble for us to have it, yeah, I would say it seems necessary. I think science has been making great strides towards explaining consciousness.

Why don’t you think brain states suffice on their own?

Well, what is “awareness”? What “non-material” product would this be? I think this is a problem neuroscientists and those that work with artificial intelligence have been working hard on.

Jayman: One thing I wonder, as someone interested in linguistics: Your prose is v. good, so have you studied English usage or do you simply write well by instinct? Are you related to any professional writers?

The replies below may be TL;DR but I had no choice. (& I can’t see a way to reply to your reply.)

That would then make the problem one of semantics, yes? Specifically, what do we mean by “universe” and something that is “outside” of it?

I’d claim that the semantics govern whether one can reasonably state, within science, that ‘Nothing in the universe “goes beyond” the laws of physics.’ If it’s a tautology, one can reasonably state that but it’s redundant. If it’s not a tautology, one is being papal rather than scientific.

Our brains work because of the laws of physics, but they grant us something beyond matter that isn’t obviously derivable from physics-as-phenomenon.

***

Brains do? What evidence is there of that?

The evidence is mathematics. We are aware of pi or sqrt(2) by extra-sensory, extra-material intuition, because mathematics logically precedes physics. Logic governs matter, not vice versa. Or rather: inter-relating entities, of any kind, necessarily behave in “logical” ways. Maths is a symbolic system designed to model that inter-relation or bring it to the surface. So when humans use maths, their brains are in a sense going beyond physics, or accessing something more fundamental than physics.

Yes, but there is something very mundane but very mysterious in, or of, the brain: consciousness and its role in cognition and behaviour. Is it causal or simply epiphenomenal, for example? Scientifically speaking, consciousness doesn’t seem necessary and doesn’t seem possible to explain.

****

Since we have it, and since evolution apparently went to a lot of trouble for us to have it, yeah, I would say it seems necessary.

Evolution gave us blood. Blood is red. Is the redness important? No. Evolution gave us brains. Brains are conscious. Is the consciousness important? Not proven. Of course, humans think it is, but humans also think they have free will (an illusion) and personal identity (another illusion). OK, I myself think consciousness is important, but I’d be amused if it turned out not to be, because I like counter-intuitive results and that would be the biggest of all.

I think science has been making great strides towards explaining consciousness.

I don’t agree. Science has made great strides towards explaining the brain, but that isn’t the same thing.

If it’s a product of (a particular sub-set of possible) material brain-states, why don’t the brain-states suffice on their own?

***

Why don’t you think brain states suffice on their own?

Because they’re accompanied by consciousness, which, as you say above, suggests (but does not prove) that it’s important. But I cannot see why the mechanism has to run with consciousness. No-one can: we merely experience that being the case and conclude that it’s necessarily the case.

It doesn’t seem to be, but how is a brain-state aware of itself or aware of its own (non-material) product?

***

Well, what is “awareness”? What “non-material” product would this be?

Scientifically, “awareness” is receipt-and-processing within the brain of information from a source that is usually external to the brain. So the brain is aware of, e.g., blood-chemistry. To be aware in a higher sense is to receive-and-process and then be conscious of the result, i.e. the product of the brain-state. You can define and investigate the brain-state, but you can’t define “consciousness”: you can only experience it. And it isn’t experienced as material or as something objective. Either we know consciousness from the inside or we infer it from behaviour. So knowledge of it is either subjective or inferential, i.e. it’s never scientifically rigorous.

I think this is a problem neuroscientists and those that work with artificial intelligence have been working hard on.

Yes, but making no progress on. I’m not being anti-science: consciousness is perhaps the most important problem of all and I’d like science to explain it. Perhaps I shouldn’t. I certainly have serious doubts about what brain-science will allow the state and others to do. Electricity is a wonderful thing, but it is a horrific tool for torturers. The most disturbing passage in Nineteen Eighty-Four is something related to brain-science:

Two soft pads, which felt slightly moist, clamped themselves against Winston’s temples. He quailed. There was pain coming, a new kind of pain. O’Brien laid a hand reassuringly, almost kindly, on his.

“This time it will not hurt,” he said. “Keep your eyes fixed on mine.”

At this moment there was a devastating explosion, or what seemed like an explosion, though it was not certain whether there was any noise. There was undoubtedly a blinding flash of light. Winston was not hurt, only prostrated. Although he had already been lying on his back when the thing happened, he had a curious feeling that he had been knocked into that position. A terrific painless blow had flattened him out. Also something had happened inside his head. As his eyes regained their focus he remembered who he was, and where he was, and recognized the face that was gazing into his own; but somewhere or other there was a large patch of emptiness, as though a piece had been taken out of his brain.

“It will not last,” said O’Brien. “Look me in the eyes… Just now I held up the fingers of my hand to you. You saw five fingers. Do you remember that?”

“Yes.”

O’Brien held up the fingers of his left hand, with the thumb concealed.

“There are five fingers there. Do you see five fingers?”

“Yes.”

And he did see them, for a fleeting instant, before the scenery of his mind changed. He saw five fingers, and there was no deformity. Then everything was normal again, and the old fear, the hatred, and the bewilderment came crowding back again. But there had been a moment – he did not know how long, thirty seconds, perhaps – of luminous certainty, when each new suggestion of O’Brien’s had filled up a patch of emptiness and become absolute truth, and when two and two could have been three as easily as five, if that were what was needed. It had faded before O’Brien had dropped his hand; but though he could not recapture it, he could remember it, as one remembers a vivid experience at some period of one’s life when one was in effect a different person. (Op. cit., Part 3, ch. 2)

http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks01/0100021.txt

Your argument is not fundamentally about HBD vs the Blank Slate. It’s about the contradiction inherent in the mind-body problem.

According to physics as we presently understand it, there’s simply no way human intentionality can cause atoms to change course. It’s a good argument, which I for one can’t refute.

I’d just say one thing for the other side. Subjectively, certain things feel more free and others less so. A glutton pigging out on a donut has a very different inner experience from a hunger striker being force fed donuts by his prison staff. The glutton still feels free to stop eating the donut while the hunger striker does not.

In evolutionary terms, acquiring that consciousness, with its concomitant sense of self-determination and intentionality, has been very expensive. It goes against Darwinian theory for us to acquire such intentional feelings, at such massive evolutionary cost, if the intentions are mere epiphenomena which can’t actually do anything.

@georgesdelatour:

I wouldn’t quite say that.

The mind-body problem is a problem of human understanding, not a physical paradox. First of all, what is “human intentionality”? You must answer that question before declaring that it’s impossible that it can affect the physical world.

Just to be clear, discussions on free will has nothing to do with “free from external coercion”. That’s not what I’m talking about.

Why? All animals with brains can direct their actions. The human issue is merely one of sophistication.

Hi Jayman

Thank you for your reply. Unfortunately I’m now more confused than ever about exactly what it is you’re asserting when you say humans don’t have free will.

You say “all animals with brains can direct their actions”. And, to me, if free will means anything, it means the ability to direct your actions. I thought you were claiming that, for every apparently volitional act of every brain-endowed animal, there are always causally sufficient antecedent conditions. Hence the appearance that the animal is directing its actions is an illusion.

If you have a moment, could you please watch this reasonably short video:

In it, John Searle explains why he thinks free will is philosophically problematic. I’ve previously assumed that you’re rejecting free will in Searle’s terms. But now it seems as if you’re accepting free will in those terms, but rejecting it at a higher, more subtle level which I haven’t yet quite grasped.

@georgesdelatour:

Searle does indeed give a fairly good description of the problem (with a few errors).

I’d go as far as to say that science has largely (though not entirely) rendered philosophy obsolete. I say not entirely because there are philosophers like Nick Bostrom who do perform work that’s still relevant today – but even this is only worth anything because it’s possible to evaluate his arguments mathematically.

One place where Searle gets it wrong is that he paints free will existing in some dichotomy with determinism, when that’s not the problem (well, depending on how you define determinism). For one, the universe isn’t deterministic in the sense that all events follow one pre-ordained plan from beginning to end. The universe is random thanks to quantum mechanics. However, if you take determinism to mean all events occur thanks to causal factors (which operate probablistically), then sure, then yes, free will would be in conflict with this. Since that is actually the case, then there is no free will.

Hence, this is the case.

However, a lot of people think of free will in terms you do:

This is indeed what a lot of people think, including what Baumeister apparently believes. However, it’s not a useful definition, because this is a given.

As well, more importantly, as I argue here, the ability “to direct your actions” occurs within a tightly bounded parameter space, thanks to the structure of your brain, a structure which is heavily specified by genetics.

“However, if you take determinism to mean all events occur thanks to causal factors (which operate probablistically), then sure, then yes, free will would be in conflict with this. Since that is actually the case, then there is no free will.”

The problem is that there are the quantum variables, and nobody I know of can say why they turn out the way they do beyond probabilities. If you have probabilistic variables then you haven’t got strict causality. The number of possibilities in any instant is literally infinite.

Douglas Adams in the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series had fun with the fact that odd things can happen (albeit with extremely low probability) such as a whale or a pot of petunias appearing in the clouds over the surface of a planet. What is the cause? I can’t say. If you can, Jayman, please get that Nobel! We all love it when our favorite bloggers make a name for themselves off the Internet.

I am also not sure what Jayman exactly means by “free will does not exist”. Also, I think Jayman is refusing to accept that providing all the data about what is happening in my brain when I experience something, still does not equals what _I_ experience as _experiencing_. Second, there is a problem of semantics. If we go back to layman definition, then surely when I am presented a choice between getting thirty lashes or a portion of ice cream, i will choose ice cream, and still I would consider myself as exercising my free will. That I have preferences, some of them even preventing me from making some choices, still does not mean I am not “free”, since those preferences constitute part of what is “me”.

That my choices result from my brain structure, my genes etc means nothing, since “me” is exactly my brain structure; _I_ was created by genes. There is no _I_ besides my brain, at least for materialist.

Now, if you would create a definition of “free will” which would contradict layman feeling of what “free will” is, then you are discussing against a strawman. So, Jayman, what is your definition of “free will” and what would mean, to you, that someone has a “free will” ?

Agreed

Our current understanding of causation at the subatomic level doesn’t fit with free will. But our understanding is incomplete. And if it turns out the physics does permit something like conscious volition to exist, four billion years of natural selection will almost certainly have found and exploited that possibility.

I agree with the HBD community that our conscious attributes have been subject to heavy genetic selection. But that at least suggests that our conscious attributes might have real causal power. If they’re epiphenomenal, and they can’t actually “do” anything, why would they be subject to such heavy selection? That’s not a decisive argument, but it is suggestive.

I also see Searle’s point, that you can’t actually live in the real world acting as if you don’t have free will. Because choosing to act as if you don’t have free will has all the apparent attributes of free will. The philosopher who refuses to choose an entree at the restaurant because he’s a determinist seems every bit as volitional as the other members of the dinner party who choose the steak or the fish.

If I read Jayman’s blog post and decide everyone’s voting choices are predetermined, that new awareness might make me decide not to bother voting next time. But my decision to abstain would then appear to be a choice, a conscious response to the persuasiveness of his arguments.

At the everyday level of human interaction, we don’t have AS MUCH free choice as we sometimes assume. We’re subject to unconscious biases and invisible appetites – the stuff of neuroeconomics. But the point is, at least some of us can become conscious of our unconscious biases, and choose to modify our behaviour. So that attack on free will isn’t decisive.

It’s that subatomic level, of “billiard ball” causation, which looks to be incompatible with free will. And if it finally is incompatible, free will really is an illusion.

@georgesdelatour:

You’re getting a bit lost in the notion. Conscious volition does exist, and the non-existence of free will doesn’t factor into that. The fact that behavior follows a semi-deterministic course doesn’t mean the process, what we call “conscious volition” is not important.

The rest of your comment stems from that misunderstanding. Complex and sophisticated doesn’t mean “not determined”.

Why did you make that choice (or for that matter, any choice)? That’s the crux of the issue.

Even if they are “predetermined” (which they are not strictly), what predetermines them? Input still matters.

@szopeno:

Why?

Notice there is a little bit of weaseling here. Specifically, what do you mean by “providing all the data about what is happening in my brain when I experience something?”

This is Baumeister’s argument. I don’t think it’s useful to try to define free will as “free from coercion”. More specifically, there’s the issue of “suppressing impulses” which itself is operationally useless from any consideration of free will. As Sisphyean notes, even the most coldly and deeply contemplated rational decision follows a predictable pattern, to say that the ability to suppress impulse equals free will is foolhardy.

“Free will”, in any meaningful sense, would mean that behavior would be unpredictable, at least statistically, from physical laws and knowledge of the individual, including genetics. Since that’s clearly not the case (even people we describe as “unpredictable” operate rather predictably), free will simply does not exist.

I don’t think you proved your point, not nearly. Your (really long) post here is merely a mass of descriptions of certain phenomena and definitions. And in a way it verges on word salad because there is no linkage between many of the items you listed here.

I agree with your basis thesis, which, if I may restate, is this: humans see themselves are logical creatures of free will, but in truth they are all operating as tools of their genetic code, operating at the behest of biological imperatives, reproduction, tribal/cultural units acting on behalf of their reproductive instincts, on behalf of the unity and cohesion of their tribes/cultures, etc.

But you did not prove it. Not even close.

I am not sure you can prove it. We don’t have enough distance from the problem. There are not enough tools of abstraction available to us to help us handle the problem.